Contraflow cycling across Europe – a low-hanging fruit still to pluck

One of the parameters we analyse in our QECIO (Quantifying Europe’s Cycling Infrastructure using OpenStreetMap) dashboard is the uptake of contraflow cycling: the percentage of streets on which cycling in both directions is allowed in the total length of local one-way streets. Contraflow is a low-cost measure promoting cycling and increasing safety. It allows more direct cycle trips and enables cyclists to avoid dangerous main roads and intersections.

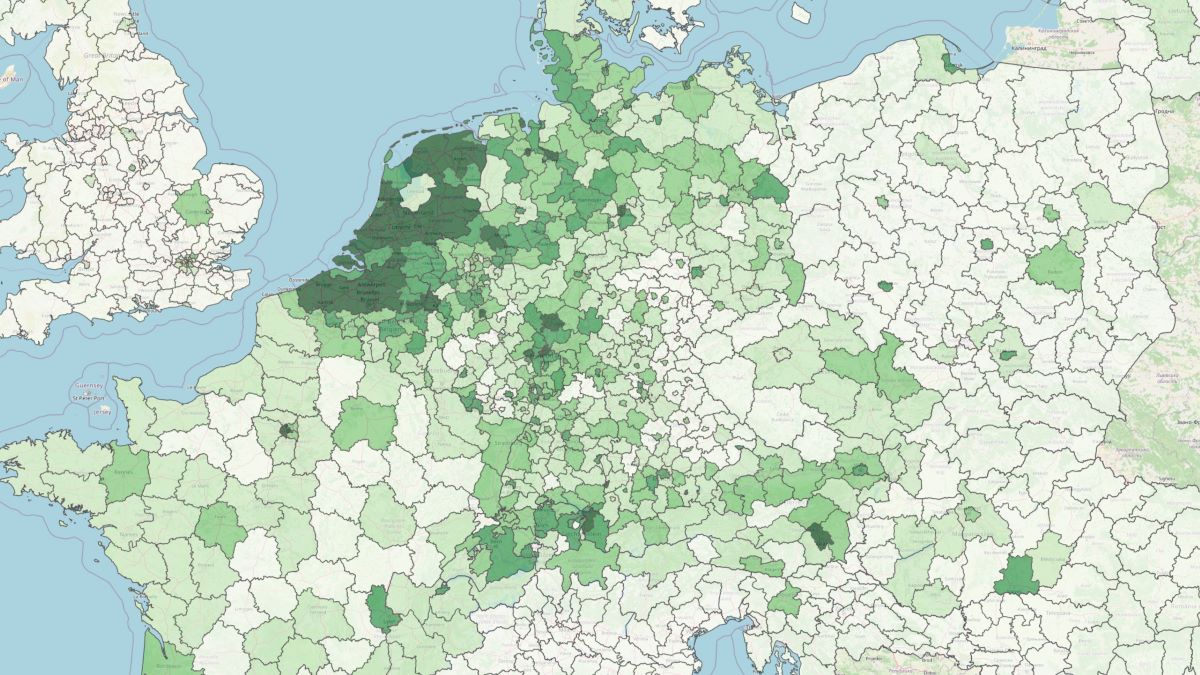

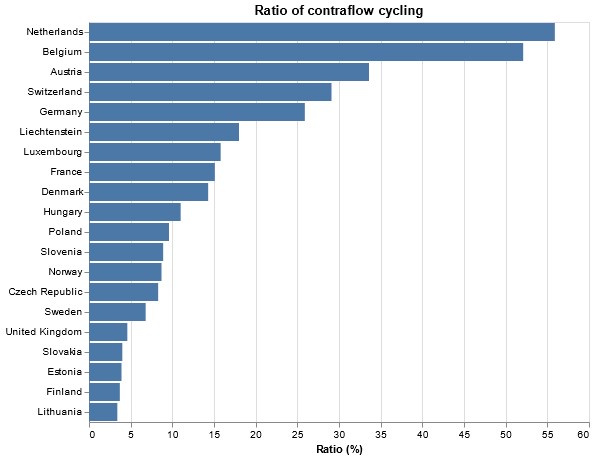

The contraflow cycling ratio can be considered a measure of the cycle-friendliness of traffic management in the area. Unfortunately, on average, only 10% of local one-way streets across Europe allow contraflow cycling. In the leading countries, the ratio exceeds 50%, and in some regions even 70%.

What is it?

Contraflow cycling means allowing cycling in both directions on one-way streets. The idea stems from the observations that:

- a street might be too narrow for two cars to pass each other but still wide enough for a car and a bicycle;

- one-way streets often serve to filter out traffic from residential areas. At the same time, it is necessary to protect local streets from motorised traffic; cycling does not generate noise or pollution.

In most cases, contraflow can be implemented on local streets by only applying a panel with an exception for cyclists under one-way and “no entry” signs. If there is space, a contraflow lane for cyclists can be painted. In some cases, a cycle track provides physical segregation.

Simple contraflow cycling in Tilburg, Netherlands.

What is it suitable for?

Contraflow cycling allows more direct cycle trips and enables cyclists to avoid dangerous main roads and intersections. Making some street sections one-way for cars (preferably with alternating directions) with contraflow cycling allowed can create longer cycling corridors through quiet local streets.

Just a few examples: contraflow cycling kickstarted the Brussels regional cycle network. Routes leading through local streets connected different districts and contributed to more than a threefold increase in cycle traffic. In Leuven, also in Belgium, streets with contraflow cycling were an essential part of the circulation plan, which eliminated through car traffic from the city centre and increased cycling volumes by 32% in one year.

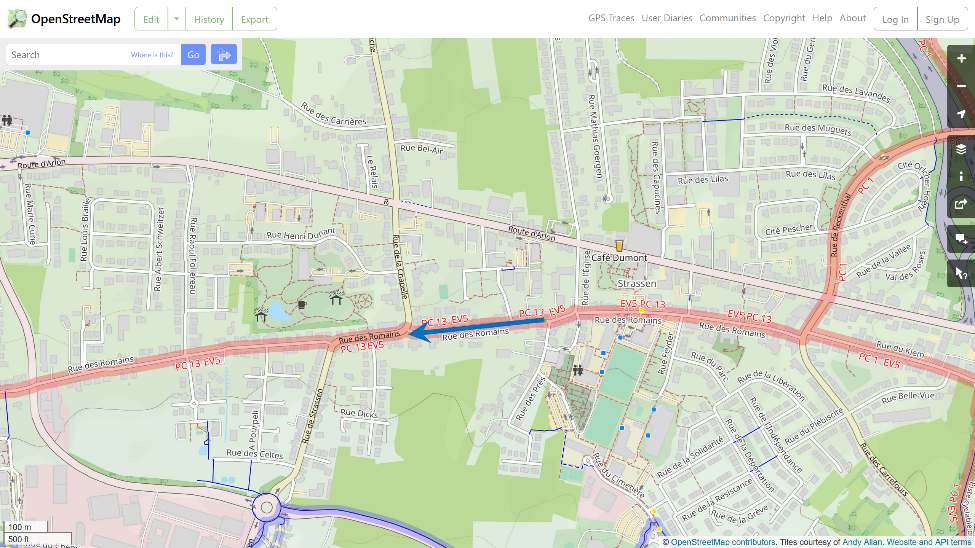

In Luxembourg, a short but strategically located one-way section of Rue des Romains with contraflow cycling filters our car traffic. It enables cyclists to access the city centre safely from the west. This way the main cycle route (EuroVelo 5) has been decoupled from the busy Route d’Arlon (national road number 6). In Kraków, Poland, the contraflow lane on Kopernika Street is among the most popular sections of the cycle network, with over 400 cyclists per peak hour. In Warsaw, relatively quiet Nowogrodzka Street provides an alternative for the central area of Al. Jerozolimskie, a six-lane arterial road. In London, Quietways made regular use of contraflow cycling.

A one-way section of Rue des Romains with contraflow cycling filters our car traffic and enables cyclists safe access from the west to the Luxembourg city centre. This way the main cycle route (EuroVelo 5) has been decoupled from the busy Route d’Arlon.

Is it safe?

While navigating narrow streets might be awkward and sometimes not the fastest, it is safe. Drivers and cyclists have much better mutual visibility when the cyclist is going “against the traffic” than with the traffic. On top of that, most car doors open in a way that is much safer for cyclists in contraflow, so the risk and consequences of “dooring” are lower.

This is not dependent on having an established “cycling culture”: Brussels authorised contraflow cycling on 404 km of one-way streets between 2004 and 2007, starting when cycling constituted only 1.7% of all trips. The Belgian Road Safety Institute evaluated the impact (“Safety aspects of contraflow cycling. Detailed analysis of accidents involving cyclists on cyclist contraflows in the Brussels-Capital Region (2008, 2009 and 2010)”) and concluded that there were proportionally fewer accidents involving a cyclist travelling against the motorised traffic than with the traffic. The study also found that the risk of a cyclist being involved in an accident is four times greater per kilometre travelled on the primary network than in contraflow cycling on a local street. Therefore, authorising contraflow cycling on parallel local streets can significantly improve safety by creating an alternative to cycling on the main roads.

Another more recent study analysed 22 years of data involving 508 one-way streets in London and – what a surprise – came to similar results. In conclusion, the scientists recommended implementing contraflow cycling on all one-way streets and considering converting appropriate two-way streets to one-way with contraflow cycling to improve cycling networks and routes. According to the authors, governments should explore legislative options to make one-way streets two-way for cyclists by default.

This reinforces the recommendations of the PRESTO project, which concluded that the best way to increase safety is to generalise the principle of contra-flow cycling in all one-way streets.

What is the uptake of contraflow cycling across Europe?

The Netherlands has the highest share of one-way streets, with contraflow cycling permitted, closely chased by Belgium. Brussels and most of Flanders are already above the Dutch average! After those two leaders, three close competitors followed: Austria, Switzerland and Germany. Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, France and Denmark form the next peloton, and Hungary closes the top 10 as the only representative of Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, 27 of the 37 analysed countries have less than 10% of local one-way streets opened for cyclists. Implementation of contraflow cycling in these countries is a low-hanging fruit for cycling promotion and safety.

20 European countries with the highest ratio of contraflow cycling allowed on one-way streets.

The country average does not always represent the contributions of individual cities. For example, while Poland did not reach the top ten, major cities are already quite advanced. Gdańsk, inspired by the Belgian models, was the first to introduce contraflow systematically, with 127 streets opened in 2009. Radom adapted all its one-way streets to cycling in both directions in 2014. Interestingly, after winning a popular vote, the “Radom contraflow revolution” was funded from the local participatory budget and cost only around 17 thousand euros. Many other Polish cities followed, including Kraków, Łódź, Poznań, Warsaw and Wrocław.

Similarly, the average contraflow ratio for Germany is only 26%. But, for example, the district of Gießen scores 69% already. Bremen, Frankfurt am Main, Oldenburg, Rosenheim or Wiesbaden can also easily compete with Dutch cities.

Full results can be explored through the QECIO dashboard.

Disclaimer

The QECIO data was automatically extracted from the OpenStreetMap – a free, worldwide, crowdsourced geographic dataset. OSM data is more detailed and up-to-date in specific contexts than official municipal data. However, OSM data is imperfect and our extracting algorithms are even less so. The results are up to 25% lower than human-made estimates (see Methodology for explanation). Nevertheless, the order of magnitude is clear, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the only comparison that applies a consistent way of counting across different countries.

Topics:

Contact the author

Recent news!

Upcoming events

Contact Us

Avenue des Arts, 7-8

Postal address: Rue de la Charité, 22

1210 Brussels, Belgium