TEN-T and cycling: mapping good and bad practices across Europe

ECF highlights good and bad practices from across Europe of where the Trans-European Transport Network interacts with cycling.

The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) is the EU's primary network of roads, railway lines, inland waterways, ports, maritime shipping routes, airports and railroad terminals. Unfortunately, cycling is not yet included in the network, but currently the guidelines are being reviewed by the EU institutions. The European Cyclists' Federation (ECF) advocates for cycling to be properly integrated in TEN-T in order to promote active mobility and achieve modal shift towards sustainable transport.

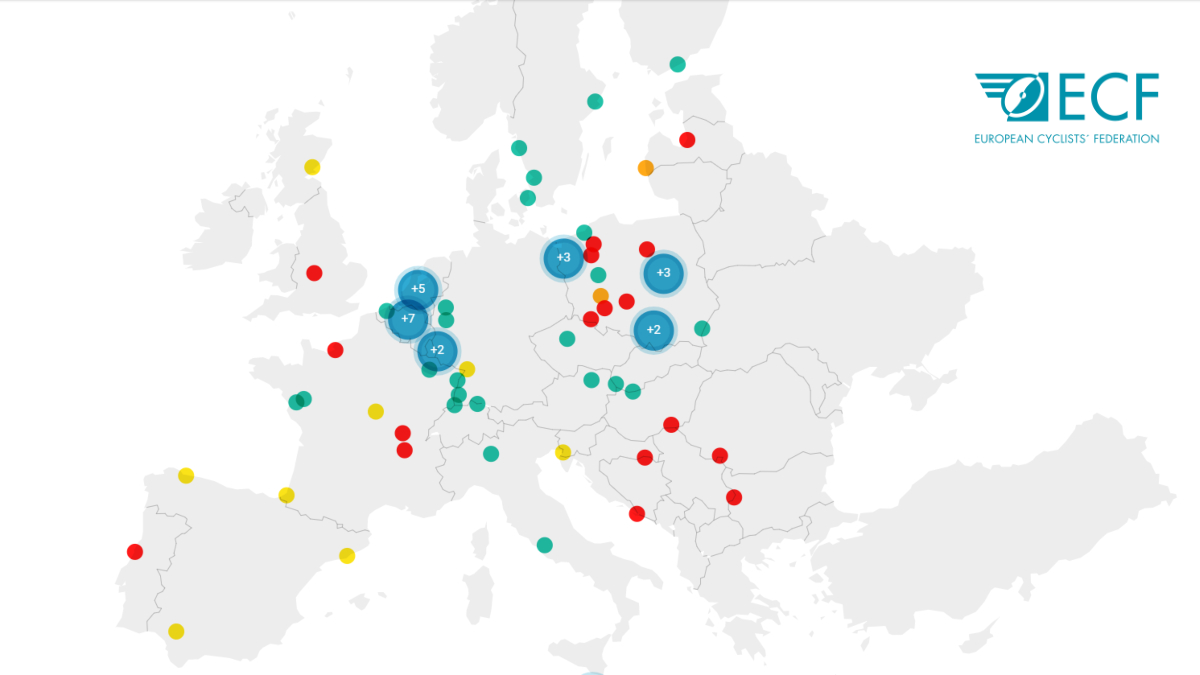

ECF has identified nearly 8,000 locations across Europe where TEN-T roads, railways or inland waterways interact with EuroVelo, the European cycle network, and many more where they affect national, regional or local cycle routes. To support our lobbying efforts on the revision of the TEN-T guidelines, ECF collects and documents concrete case studies from those intersections. In doing so, we analyse the impact TEN-T projects have on cycling, such as creating new barriers for cyclists, the cost of fixing mistakes of the past and – especially for the best practices – the technical solutions applied.

Thanks to contributions from the European cycling community, cities and regions, the number of case studies documented on our interactive map of good and bad practices more than doubled in 2022, from 36 to 76, across 25 different countries. Nearly half of them are good practices that can serve as an inspiration when developing new TEN-T projects. But it is also important to learn from mistakes, and we still see bad designs being implemented across Europe.

The western Årsta bridge in Stockholm includes a cycle and pedestrian track next to rail track, offering active modes a shortcut unavailable for cars. (Source: Aleksander Buczyński, ECF)

TEN-T roads

Most of the cases (46) concern TEN-T roads. In many cases, the development of new motorways and expressways means new barriers for cyclists, cutting suburbs from city centres or sabotaging the development of regional cycle route networks. These mistakes are complicated and expensive to rectify, as we have seen in the case of the Brussels ring road.

Despite the current TEN-T regulation encouraging the inclusion of bicycle infrastructure within civil engineering structures, such as bridges or tunnels, new landmark EU-funded TEN-T bridges are still not including cycle tracks. For example, in Croatia, neither the Svilaj bridge on the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was opened in 2021 personally by Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, nor the Pelješac bridge from 2022, connecting the southernmost part of Croatia with the rest of the country, have infrastructure for cycling.

Elsewhere, our map shows how modernisation projects, even on established EuroVelo routes, often represent missed opportunities. Examples of cycling being overlooked when renovating road infrastructure include the coastal A11 highway in Latvia (part of EuroVelo 10 and 13) and the Ponte Edgar Cardoso in Figueira da Foz in Portugal (EuroVelo 1).

On the other hand, good practices include the Ponte di Castel Giubileo on the greater ring road around Rome, or the recent Monoštor bridge on the Hungarian – Slovakia border. Interestingly, some of the best examples of integrating cycling in major road projects are not the newest ones. In Denmark, high-quality cycle tracks were built together with motorway number 16 already 60 years ago! In Slovakia, Prístavný and Lafranconi bridges, which enable cycling one level below the D1 and D2 motorways, were developed in the 80’s.

TEN-T railways

Railways (35 cases) are often attractive corridors for cycle highways, connecting the towns along the rail line and extending catchment areas of train stations. In Flanders, Belgium, 31% of the regional cycle network is located alongside TEN-T railways (with a further 20% along TEN-T inland waterways, see below). Sections of service roads alongside TEN-T railways have been adapted for cycling also in France (for example EuroVelo 6 between Oudon and Ancenis) and Germany (for example RS1 between Mülheim and Essen). The Årsta bridges in Stockholm provide quadruple rail tracks and a significant shortcut for cyclists.

But not all rail investments have a positive impact on active mobility. An upgraded 10 km section of Rail Baltica in Poland, a flagship EU project, cut three towns in half, leaving only one safe crossing for cyclists (and five for cars). Further along the same line, in Rembertów, a badly designed EU-funded tunnel project threatens to create a dead end to another EU-funded cycle track. In Belgium there have also been some missed opportunities, for example, between Brussels and Ottignies. A lot still has to be done to improve cycle traffic to and around major stations. Projects like the much-anticipated Kaisa cycle tunnel in Helsinki can serve as an inspiration..

TEN-T inland waterways, ports and airports

Rivers and canals (25 cases) are natural corridors for cycle routes. Many EuroVelo routes follow major rivers: EuroVelo 6 along the Loire and Danube, EuroVelo 15 along the Rhine, EuroVelo 17 along the Rhône, EuroVelo 19 along the Meuse, often following towpaths or water management roads. Bad examples in this area mostly concern bridges or tunnels without cycle tracks.

Ports (9 cases) and airports (5 cases) are not only travel hubs, but also points of concentration of workplaces. Milan Bergamo Airport is a certified Cycle Friendly Employer, recognising both the importance of cycle commuting and the contribution of cycle tourism to Italian economy. A cycle tunnel under one of the Schiphol runways offers an important shortcut and is a part of the recreational network around the airport. On the other hand, a 4 km cycle track from the centre of Warsaw ends 900 m before the airport, leaving the last section to be braved on a six-lane highway. Crossing the entrance to the German Karlsruhe port on the Rhine waterway requires carrying bicycle up and down steep stairs. And in Trieste, Italy, a ferry is necessary to bypass the barrier created by the harbour between the city centre and areas further south along the coast.

Would you like to add an example from your city or region? Let us know by contacting ECF Policy Officer for Infrastructure Aleksander Buczynski: a.buczynski@ecf.com

Regions:

Network/Project Involved:

Topics:

Contact the author

Recent news!

Upcoming events

Contact Us

Avenue des Arts, 7-8

Postal address: Rue de la Charité, 22

1210 Brussels, Belgium