Regional cycle networks: For commuting, tourism or recreation?

As bicycles continue to evolve as means of transport, ECF takes a look at the different infrastructure user groups that must be considered when developing widespread regional cycle networks.

Many existing policy guidelines cover the principles of planning and designing cycling infrastructure. However, most of them have been developed with a focus on urban areas and at the municipal level. With the arrival of electrically-assisted bicycles and the cycle tourism boom, there is now a clear need for planning cycling networks at the regional level as well.

But who will they be for? In the “Integrated Cycling Planning Guide”, we take a look at the three main target groups for regional cycle networks: commuters, tourists, and recreational cyclists.

For commuting

Bicycles have traditionally been considered as a local means of transport. But things have changed with the growing popularity of electrically-assisted bicycles (also known as pedelecs), which add a small electric boost whilst pedalling. Pedelecs allow riders to cycle faster with lower energy expenditure, making cycling a viable option for commuting even longer distances. For example, on the F3 cycle highway between Brussels and Leuven in Belgium, the average distance of a home to work commute by bike is as high as 22.8km.

To tap into the potential of e-bikes, functional cycle networks need to expand from core urban areas into suburbs or whole regions. They also need to provide a higher standard of infrastructure, allowing for higher speeds and mixing cyclists travelling at different speeds. This has led to the introduction of a new mobility product, cycle highways, which combine different types of infrastructure to provide a high-quality functional cycling connection.

Currently, the most extensive cycle highway network under development is in Flanders, Belgium. 110 planned routes will form a network of 2,400 kilometres. Of the 110 routes, 61 are already in use. Elsewhere, cycle highways are also a hot topic in the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, France and the United Kingdom.

Figure 1: Planned cycle highway network in Flanders, Belgium

Image 1: Fast cycle route connecting Arnhem with Nijmegen in the Netherlands, with pedelecs allowed

For tourism

The majority of cycle-route users outside of urban areas are short-distance day trippers. However, long-distance tourists making multiday trips by bicycle with overnight stays along the way generate the majority of economic benefits resulting from recreational cycling. For example, tourists only represented 18% of the 1.1 million cyclists on EuroVelo 17 - Rhone Cycle Route in 2017. Yet, this 18% of users accounted for as much as 83% of the €11.3 million generated from the route.

The cause of this disparity isn’t surprising. Day trippers might stop for a coffee, a snack or lunch, whereas long-distance tourists not only need (at least!) three meals per day, but also accommodation and occasionally other services, such as bike repair and laundry.

Therefore, the economic benefits of cycle tourism make it worthwhile to pay special attention to this specific group of users. Due to the long distances travelled and heavier luggage on their bikes, they also require higher quality standards, especially when it comes to surface material, quality and the elimination of obstacles and steep gradients. For this, the European Certification Standard for EuroVelo routes provides an overview of different criteria that a touristic route should meet.

The Polish region of West Pomerania has successfully used EU funds to rapidly create a touristic cycle network. In just five years since adopting a concept plan, 800km of high-quality cycle routes – including 350km of new dedicated cycle tracks – are either already opened or under construction.

Image 2: Cycle tourists with luggage on the EuroVelo 8 route. Photo credit: Vélo Loisir Provence

For recreation

Active recreation might not be as directly lucrative as tourism, but it is essential for physical and mental health, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An interesting concept to facilitate recreational cycling is the node network, which entails that each location (node) where cycle routes intersect has a number assigned. The user can use the node numbers to map out a cycling itinerary, deciding for themselves where to go and how long the trip should be.

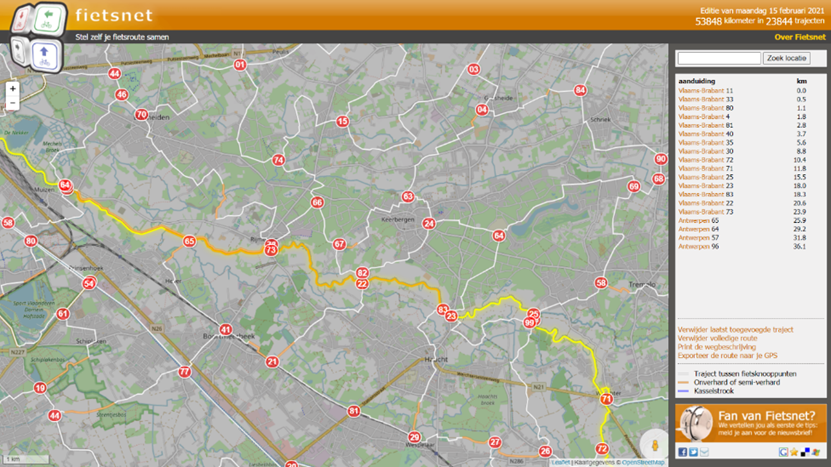

Figure 2: Part of the cycling node network between Leuven and Mechelen in Belgium. Screenshot taken from the online node route planner at fietsnet.be

The node network originated in Flanders, but now also covers the Netherlands, as well as parts of Wallonia and Germany. The Flemish network includes 3,760 nodes and nearly 5,700 connections between them, with a total length exceeding 13,000km.

The node network is a good choice for regions which already have an existing, extensive and coherent mesh of cycle tracks, greenways, agricultural roads with good surfaces and infrastructure. The RAVeL network in Wallonia (Réseau Autonome des Voies Lentes – autonomous network of non-motorised paths) represents an alternative approach to the idea, perhaps better fitted for starter or less-densely populated regions.

RAVeL started with greenways along waterway towpaths and disused railway lines and is gradually interconnecting them into a more coherent network. As for now, it includes 45 routes with a total length of 1,440 kilometres. The density of the node network is nearly ten times lower than the equivalent network in neighbouring Flanders, but when starting from scratch it is perfectly reasonable to focus on a lower number of routes and bring them to high quality, instead of dispersing funding across an extensive but under-resourced network.

Combining different functions

The fact that there are several distinct target groups for regional cycle networks does not mean that specific routes cannot combine multiple functions. Starter regions especially should begin with routes that can serve all the different groups of users to make best use of limited resources. But even within leading cycling regions, dual functionality is not uncommon.

Regions:

Contact the author

Recent news!

Upcoming events

Contact Us

Avenue des Arts, 7-8

Postal address: Rue de la Charité, 22

1210 Brussels, Belgium