Is cycling in hilly cities possible? For sure!

Last November, the Czech association Auto*Mat organized a conference focused on cycling and hilly cities, which was attended by Swiss city authorities and ECF members from Portugal and Austria. During the event, experts and participants explored this difficult topic and shared best practices coming to an (un)surprising conclusion: hills are not to be blamed for the development of cycling in cities such as Prague, Bern, or Innsbruck.

This article was written in collaboration with Daniel Mourek from the Czech Cyclists Federation

Are hills an obstacle to the development of cycling infrastructure? And are hilly cities just not suitable for cycling at all? Wandering around Europe’s hilly cities, it can be hard to imagine cycling ever taking off. But with the right vision and targeted measures, urban planners can boost the number of cyclists and thereby reap huge benefits in terms of air quality, congestion, health, and livability.

A frequent statement posed by non-cyclists in Prague is “don’t even try to support cycling in places like Prague, there is no way people will use bikes!” However, the main streets in Prague have gradients less than 5 %, which allows riding a bike at about 10 km/h. And most of Prague’s districts are comparable to those of Bern, which has a cycling modal share of astonishing 15 %. Prague is therefore very similar to that of the flat city of Pardubice located on the Elbe cycle route. Whereas bicycle use in Bern has increased by incorporating cycle lanes on the main roads, “the future goal is a higher degree of separation of cyclists based on Danish and Dutch experience,“ explains Michael Liebi, head of the car free transport unit of Bern.

Hills are not the main obstacle

Hills are not the main obstacle

Whereas hills may account for part of the factors discouraging bicycle use in hilly cities, they don’t reveal the whole picture. At the seminar, Ana Pereira, Executive Director at the Portuguese company Cenas a Pedal, explained that “hills as the main obstacle for riding a bike acknowledges only 6 % of the population. Missing cycle trails represent a much bigger problem.” Vratislav Filler, Project Coordinator at Auto*Mat, furthermore reminded the audience that a strong head wind may be as demanding as a steep inclination, and that variations in surfacing and heavy traffic likewise makes climbing more challenging.

Martin Blum, Managing Director at the Mobility Agency of the City of Vienna (ECF Cities and Regions for Cyclists member), notes that in those parts of Vienna, which are flatter, cycling is more common. However, like Pereira, he emphasizes that hills are just one factor of many. Others include the bicycle infrastructure, the attractiveness of the streets and public spaces, as well as the bicycle culture in the respective cities and countries. In any case, Blum asserts that “the Viennese hills are no excuse for more cycling. Even if the cycling potential of Berlin or Copenhagen is possibly higher, because these cities are flatter, there is still so much room for improvement.“

First create a vision, then support it

During the seminar, the international experience on how to increase cycling in hilly cities spoke simple language: “Special infrastructure for hilly parts of town only makes sense when it is a part of an overall mobility concept for low stress infrastructures accompanied by services for cyclists and promotion of car free traffic,” commented Roland Romano, Spokesman for the Austrian ECF member, Radlobby. On the Bernese experiences, Liebi summarised that “the uppermost goal shouldn’t be increasing modal share of cycling only but rather enabling all groups of users of bikes to cycle.” From presentations and discussions at the seminar, it was clear that the way to promote cycling is by considering the bicycle as an attractive and useful form of transport, which brings European cities closer to zero emissions, improved air quality, as well as more sustainable and friendlier public spaces.

To achieve such a vision, concrete measures are nevertheless needed. Suggestions include adequate infrastructure like wide cycle lanes on hilly sections aimed to improve comfort or the use of one way streets to avoid the steepest hills. Investments in bridges, cable cars such as the one in Trondheim, lifts like in Luxembourg, or cycle bypass in Prague city center can similarly easy the steep climbs.

Another powerful measure to take the strain is electric bikes. “With the e-bike there are basically good opportunities to climb hills without effort,“ says Blum. In 2014, Madrid became the first European city to launch a fully electric bike-sharing system, BiciMAD. Rather than limiting bike-sharing to the downtown area, the electric fleet incentivises Madrid’s residents to leave their car in favor of the bicycles on their daily commute across the hilly urban landscape. In Lisbon, the GIRA bike-sharing scheme, where conventional bikes are easily converted into e-bikes, has likewise proved successful.

Another powerful measure to take the strain is electric bikes. “With the e-bike there are basically good opportunities to climb hills without effort,“ says Blum. In 2014, Madrid became the first European city to launch a fully electric bike-sharing system, BiciMAD. Rather than limiting bike-sharing to the downtown area, the electric fleet incentivises Madrid’s residents to leave their car in favor of the bicycles on their daily commute across the hilly urban landscape. In Lisbon, the GIRA bike-sharing scheme, where conventional bikes are easily converted into e-bikes, has likewise proved successful.

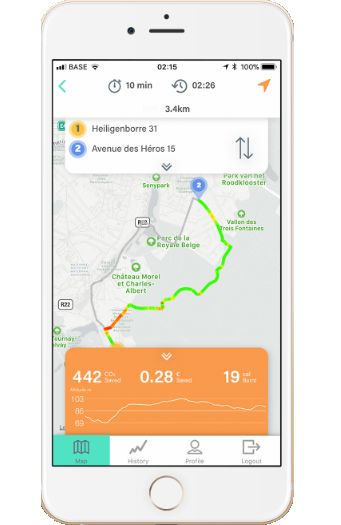

Using the newest technology to ease the path for cyclists doesn’t stop with e-bikes. Horizontal Cities have developed an app, which based on high quality topographic data provides the road of least resistance. By allowing cyclists to calculate the flattest route possible, Horizontal Cities aim to demystify that cities characterised by steep inclinations are not appropriate for cycling. Today, cyclists can take advantage of the app when navigating through Lisbon, Brussels, Madrid, Berlin, and Zürich.

So yes, hilly cities are definitely suitable for cycling! With more focus on innovative measures that can ease the climbs, the prospects for increased cycling in hilly European cities are tremendous.

Regions:

Network/Project Involved:

Contact the author

Recent news!

Upcoming events

Contact Us

Avenue des Arts, 7-8

Postal address: Rue de la Charité, 22

1210 Brussels, Belgium